The Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game genre is not dead in 2025. It is something far worse: a patient on corporate life support, its vital signs—subscription numbers and quarterly earnings—masking a soul long since departed. This truth was delivered with finality on October 28th, when Amazon announced it would “halt a significant amount” of first-party AAA game development, specifically targeting MMOs, and begin mass layoffs, putting the final nail in the coffin of its long-anticipated Lord of the Rings MMO and casting even the recovering New World into a precarious future. The diagnosis is not a lack of technology or ideas, but a fatal embrace of corporatization, ideological capture, and the ultimate betrayal of the players who built these worlds.

This decay is particularly profound because an MMORPG is not a typical consumer product. It is a covenant—an ongoing, symbiotic relationship between player and studio. Players invest years of their lives, emotional energy, and social capital into building a home within these worlds. In return, they rightfully expect the studio to act as a faithful steward. The retreat of Amazon, one of the last “sugar daddies” with the capital to even attempt this covenant, proves the stewards have all gone home. The patient on life support is not just a piece of software; it is a violated trust.

The unique, revolutionary promise of the MMORPG was not merely a new type of game; it was a new type of place. It offered a persistent, shared world—a voluntary, collective undertaking where people could escape the tedium and constraints of the real world. For a few hours each night, they were not accountants or students; they were heroes and adventurers. The shared challenges—the grueling corpse runs, the epic, multi-hour raids, the simple act of navigating a dangerous world—forged unbreakable social bonds and a profound sense of community. This social stickiness, this feeling of belonging to a world and a group of people within it, is what propelled MMORPGs beyond being mere games and into essential social experiences. It is precisely this promise that has been systematically betrayed.

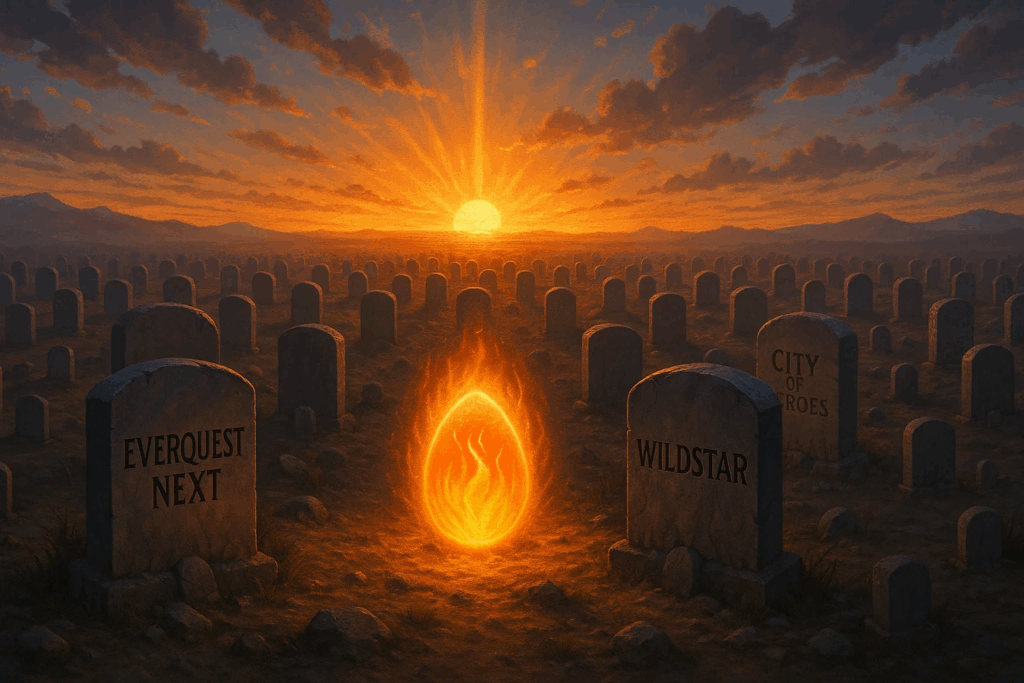

We are not here to mourn. We are here to perform an autopsy, to chronicle the collapse in real time, so that future builders might understand what was lost and why.

The Life Support Machines: A Façade of Health

To the casual observer, the genre appears stable. World of Warcraft, in both its Retail and Classic iterations, continues to operate. Final Fantasy XIV maintains a dedicated following. These titans are the genre’s iron lungs, massive mechanical systems that breathe for a comatose body. Their continued existence is mistaken for health. In reality, they are monuments to a departed era of design brilliance. They are sustained by sunk cost, addiction, and community inertia, not by a vibrant, innovative present. New AAA attempts either crash on arrival or are stillborn in development, unable to compete with the ghost of what once was. The machines are keeping the body alive, but the soul has long since fled.

The Subtraction of Challenge: The Great Unmaking

The core sin of modern MMO design is not a flaw; it is a philosophy. It is the relentless, twenty-year project of subtracting challenge. The original MMORPGs—EverQuest, Ultima Online, the early years of WoW—were built on a foundation of friction. Dangerous travel, punishing death penalties, intricate character builds, and demanding social requirements were not design oversights. They were the ingredients of a compelling world.

The drive for accessibility has undeniably broadened the genre’s appeal. Games like Final Fantasy XIV have been rightly praised for creating a welcoming, story-driven experience that functions as a form of social therapy for many. However, this pursuit of accessibility has come at a catastrophic cost: the systematic erosion of the very elements that defined the genre.

Modern design has systematically eliminated every one of these elements in the name of “accessibility” and “quality of life.” The result is a hollowed-out experience:

- The Erosion of Mastery: When talent trees are simplified into linear paths and every piece of gear is quickly replaced, player choices become meaningless. There is no consequence for a bad decision, and therefore no prestige in a good one. The game becomes a guided tour, not a test of skill.

- The Death of the World: The virtual world is no longer an antagonist to be conquered. Level-scaling and safe, curated zones have transformed vast, dangerous continents into a pre-school playground. The sense of awe and exploration born from risk has been replaced by the bland safety of a theme park.

- The Commodification of Community: The automated Group Finder and cross-realm zones did not improve community; they annihilated it. By making every player a disposable, anonymous unit, they destroyed the need for reputation, social capital, and server identity. The “massively multiplayer” aspect has been reduced to playing a single-player game with other people as background noise.

This is not evolution. It is a declawing. The genre has been stripped of everything that made it immersive and compelling, all to lower the barrier to entry for the hypothetical “casual” player. The players flocking to Classic servers are not nostalgics; they are refugees fleeing this hollowed-out reality, voting with their time for a world that still has teeth. They are rejecting the modern “amusement park ride” in favor of a world where the journey itself—with all its friction, danger, and unscripted social demands—is the point.

The Narrative Hand Holding: From Living World to Scripted Spectacle

A quiet but profound coup has taken place in the designer’s chair: the player has been demoted from protagonist to audience member. The original promise of the MMORPG was the virtual world—a persistent sandbox where players, through their actions, alliances, and conflicts, would become the protagonists of an emergent, unfolding story. The lore was a backdrop; the players were the autonomous actors.

The modern MMORPG has inverted this. It has become a narrative delivery system, a tightly scripted spectacle where the player’s role is to dutifully consume a pre-written story, episode by episode.

- The Illusion of Agency: Modern quest design is a series of glorified cutscenes. The player is shepherded from one story beat to the next, making no meaningful choices that impact the world. You are not shaping history; you are following a guided tour through a history that was written without you.

- The Drip-Feed Model: Content is now released in episodic chunks, a model borrowed from television. This is not done for creative effect, but to maximize player retention metrics. It transforms the game into a chore, a weekly checklist to complete before the next episode drops. The living, breathing world is replaced by a content pipeline.

- The Death of Emergence: In a sandbox, the most memorable stories are player-generated: the epic guild wars, the unlikely alliances, the rare loot drops that became server legend. The scripted, drip-fed narrative actively murders these opportunities for emergence. There is no room for player-driven drama when the story is on rails, racing toward its pre-ordained conclusion.

This is the ultimate consummation of that design cowardice. It is the subtraction of purpose. The player is no longer the hero of their own adventure; they are a spectator to someone else’s. These worlds are essentially Potemkin villages—beautiful, sprawling facades where only a few structures (raids, dungeons) are truly operable, and the rest is smoke and mirrors designed to guide you seamlessly from one scripted event to the next.

The “Loner” Mandate: The Business Case for a Sterile World

This systemic erosion was not an accident; it was a deliberate strategy, one perfected by World of Warcraft (2004) and later codified in forums like the 2011 GDC talk by BioWare’s Damion Schubert on designing for “The Loner.” World of Warcraft was, from its very launch, the ultimate expression of this philosophy. The argument was seductive and, from a pure business perspective, brutally logical: to achieve mass-market scale, an MMO must cater to the player who wants the aesthetic of a living, breathing world but actively avoids the friction or social obligation of cooperating with others.

Blizzard’s implementation was the infamous “greased chute”: a polished, accessible solo leveling experience meticulously designed to require no communication, no dependence on others, and no need to form a single meaningful social bond to reach the level cap. This design philosophy provided the intellectual justification for three catastrophic shifts:

- The Elimination of Necessity: Game design pivoted from requiring cooperation to merely allowing it. Grouping was transformed from an organic, survival-based imperative into an optional, curated activity managed entirely by automated group finders. The world no longer demanded you find allies; it only permitted you to summon them.

- The Illusion of Life: The “living, breathing world” was replaced with a sophisticated diorama of scripted events and chatty NPCs. This gave the solo player the curated aesthetic of a vibrant world while surgically removing the unpredictable, player-driven chaos and emergent storytelling that are the hallmarks of a world that is truly alive.

- The Invitation to Anonymity: By designing for the lone player first, the game inherently dismantled the ecosystem of reputation and server identity. If no one needs anyone else, then no one is compelled to be accountable, friendly, or trustworthy. Accountability vanished into the void of cross-realm anonymity.

The business case was proven correct in the short term—it did achieve unprecedented if hollow scale. But the long-term cost was the genre’s soul. By catering to the player who wanted to be left alone, they destroyed the very conditions that created the deep, sticky communities which made people want to stay for a decade. They granted the wish of the loner and in doing so, made the world a lonelier, and ultimately less compelling, place for everyone. They built a beautiful, populated theme park and called it a world, fundamentally misunderstanding that the magic was never in the rides themselves, but in the shared struggle and trust forged with the people you were forced to rely on to survive them.

The Broken Covenant: From Steward to Service Provider

The most profound transformation in the MMORPG genre has been the redefinition of the player’s relationship to the virtual world. We have witnessed the systematic replacement of the player-as-citizen with the player-as-customer—a shift that fundamentally altered the social contract underlying these persistent worlds.

The Player-as-Citizen (The Classic Model):

In the original MMOs, players were citizens of a world that demanded participation. This relationship carried specific obligations:

- You had responsibilities: Competence, reliability, and contribution to your guild or community were expected. Your reputation was social currency earned through action.

- You operated under a social contract: Your rights to participate in endgame content, receive help, and enjoy the world were earned through your contributions to the community.

- The world had authority: It was a place with inviolable rules. You adapted to its dangers and rhythms; it did not adapt to you.

The Player-as-Customer (The Modern Model):

The corporatization of the genre reconfigured this relationship into a purely transactional one:

- You have expectations, not obligations: As a paying customer, you expect entertainment, convenience, and satisfaction. The burden of performance shifts entirely to the developer.

- There is no social contract, only a Terms of Service: Your relationship is with the corporation. Other players become part of the service’s background ambiance.

- The world is a product to be consumed: It must be sanitized of frustration, inconvenience, or any demand that might dissatisfy the customer.

This transformation explains the hollow feeling of modern MMOs. By catering to the customer’s desire for zero obligations, developers systematically dismantled the very fabric of virtual society. A functioning community cannot exist without mutual obligations. The modern MMO thus populates its world with two types of entities: scripted NPCs who provide quests, and “player-NPCs”—real people who provide the aesthetic of a living world but interact with all the meaningful engagement of background characters.

The tragedy is that in satisfying every customer demand for convenience, the industry created the very emptiness players lament. The player-as-customer received exactly what they asked for—a world with no demands—and in doing so, was cheated of what they truly needed: a world where their presence mattered.

The Co-Optation of Excellence: When the Theorycrafting Spreadsheet Ate the Soul

A critical, player-driven shift sealed the genre’s fate: the weaponization of player excellence. The community’s desire to master complex systems mutated into a tyrannical culture of hyper-optimization that ultimately served the developer’s metrics-driven agenda.

This began organically with theorycrafting—treating the game as a solvable equation to overcome its toughest challenges. The corruption came in waves:

- The Rise of the “Achiever” and Algorithmic Gatekeeping: The measure of a player shifted from competence to a single, quantifiable metric: Gearscore, item level, and DPS parses. This created a culture of exclusion, where players were deemed “scrubs” and denied entry to groups based on a number, not skill or reputation.

- The Puzzle-Boxification of Adventure: Raids ceased to be wild frontiers. They became sterile puzzles to be solved. Once the mechanic was decoded—usually within days—the encounter was reduced to a farming routine. The serendipitous magic of the unknown was designed out.

- The Developer’s Embrace and Profound Disconnect: The hiring of theorycrafting elites like Ion Hazzikostas (Guild Master of Elitist Jerks) by Blizzard signaled a fundamental change: the game would now be built for the spreadsheet, by the spreadsheet. This led to a catastrophic misallocation of resources, with the vast majority of development time spent on intricate raid content for a tiny minority of players, while the world for the other 90% stagnated.

Players didn’t just “succumb” to this culture; they were given a brutal ultimatum by the system itself: conform to the meta or be cast out. The soul of the RPG—unique builds, experimentation, personal discovery—was sacrificed on the altar of optimal performance. The player base, in its relentless drive to excel, became an unwitting agent of its own creative imprisonment.

The Enshittification Pipeline: The Macro-Economic Cancer

The driving force behind the genre’s decline is not a creative misstep but a systemic economic disease. Cory Doctorow’s concept of enshittification provides the definitive diagnosis. It is a three-stage metastatic process where a platform consumes its own value until nothing remains:

- Stage 1: Attract Users with Generosity. This was the genre’s golden age. The value proposition was singular: immerse yourself in a world worth your time. From EverQuest’s punishing frontiers to World of Warcraft’s polished Azeroth, the product was the virtual world itself. Every design decision served the player, building immense loyalty and social capital.

- Stage 2: Monetize the Captive Audience. Once a critical mass of players was locked in by sunk cost and community, the pivot began. The “subtraction of challenge” was the primary tool. The player was no longer the customer to be served but the asset to be monetized. The game’s core loop was re-engineered to maximize metrics like Daily Active Users (DAU) and Average Revenue Per User (ARPU). The virtual world ceased to be the product and became a delivery mechanism for cash shops and battle passes.

- Stage 3: Abandon Users for External Stakeholders. We are now in the terminal phase. With the player experience hollowed out, growth must be found elsewhere. The platform is now optimized for external stakeholders: ESG rating agencies, activist shareholders, and the corporate media complex. The goal is no longer player satisfaction but earning political and social capital that insulates the corporation from risk. The player base is treated as an extractive resource, and its dissatisfaction is an acceptable externality.

Enshittification is the overarching narrative. It explains why the decline was not an accident but an inevitability under the current economic model. The following section details the mechanics of how this process is implemented on the ground.

The Investor-as-Designer Model: The Micro-Level Execution

If enshittification is the disease, the “Investor-as-Designer” model is the vector. Financialization has replaced creative vision. The true architects of the modern MMORPG are no longer game designers but financial analysts whose sole compass is quarterly growth, a reality underscored by the waves of post-merger layoffs at studios like Activision Blizzard that prioritize balance sheets over creative teams.

This model manifests in three concrete, destructive ways:

- The Feature Selection Matrix: New content and systems are not greenlit by asking “Is this fun?” or “Does this make the world more believable?” The approval process is a cold calculus: “Will this feature increase player retention metrics or create a new monetization stream?” The most sophisticated design work is reserved for the cash shop interface, not the open world.

- The Live Service Grind: The “live service” label is a euphemism for a predictable revenue pump. It transforms the game from an experience into a chore. Daily and weekly quests are not designed to evoke joy but to manufacture habit—a compulsion to log in that is more valuable to shareholders than player satisfaction.

- The Death of Innovation: True innovation is a financial risk. A radically new MMO could fail. It is infinitely safer to iterate on a 20-year-old template, slapping a new narrative skin on the same progression treadmills. The result is a genre filled with expensive clones, all competing for a slice of a stagnant market because no one is allowed to grow the pie.

Under this regime, developers are not visionaries. They are technicians executing a product roadmap dictated by the finance department. The “vision” for the game is a spreadsheet of Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). The soul of the world has been replaced by the logic of the quarterly earnings call. This model is the ultimate expression of a system designed not to create a better MMO, but to satisfy shareholders with predictable quarterly growth.

The Ideological Capture: The ESG/DEI Straitjacket

Layered atop the naked profit motive is an even more suffocating filter: the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) framework and its enforcement arm, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI). This is not a minor influence; it is a hostile takeover of the creative process by a political agenda that views art not as an expression of truth or beauty, but as a vehicle for social re-education.

Every storyline, character, and design choice must now pass a dual filter: the Profit Filter and the Ideological Filter. A concept can be brilliantly fun and immersive, but if it fails to align with a DEI scorecard or presents “problematic” traditional archetypes, it is killed. This has several devastating effects:

- Sterile Storytelling: Narratives become predictable, moralistic fables designed to signal virtue rather than tell compelling stories. Complex villains are replaced with one-dimensional bigots; nuanced cultures are flattened into bland, inoffensive caricatures. Conflict arises not from believable worldbuilding but from a simplistic moral algebra.

- The Inversion of Merit: The systematic purging of veteran developers is a deliberate policy. They are being replaced not necessarily by talent, but by demographic credentials and ideological conformity. The primary qualification is no longer a track record of creating beloved games, but holding the correct political views.

The product that emerges is a hollow shell: inoffensive, monetizable, and ideologically pure. It is designed to satisfy external stakeholders—investors and ESG auditors—not the players who actually log in every day.

The Human Cost: A Purge of the Craftsmen

The grim reality of this capture is confirmed by whispers from inside the remaining AAA studios. The recent waves of layoffs are not merely financial “optimizations”; they are an ideological purge. Veteran designers, artists, and writers who understand the old magic—the nuanced craft of building believable worlds and rewarding gameplay—are being pushed out. Their dismissal is frequently justified on ideological grounds; they are deemed “problematic” and “unreconstructed” for prioritizing timeless design principles like player agency and world coherence over contemporary narrative didacticism and DEI scorecards.

Their replacements are often selected for compliance, not competence. The result is not just a change in personnel but a demonstrable decline in the product. New content patches exhibit a marked drop in technical polish, creative depth, and cohesive design. The machines on life support—the legacy titles—are now operated by technicians who have read the manuals of corporate ideology but never understood the patient’s original vitality. This is the inevitable result of the Inversion of Merit: the product itself becomes as hollow as the ideology that now guides it.

The Silence of the Critics: The Stenographers of the Industry

This entire decay has proceeded unchecked because the self-appointed chroniclers of the genre have abdicated their duty. Major fan sites and news outlets like Massively OP, MMORPG.com, and Wowhead are not critics; they are unpaid stenographers for the corporate press release. Their business model is fundamentally built on access journalism, creating an insurmountable conflict of interest that guarantees a steady stream of uncritical, boosterish coverage.

- The Access Trap: These sites survive on a steady drip of exclusive reveals, developer interviews, and early access provided by the publishers. To bite the hand that feeds them with genuine, hard-hitting critique would mean immediate excommunication from the information pipeline. Their content becomes a repackaging of corporate marketing, presented as news. They are not watchdogs; they are part of the public relations apparatus.

- The Illusion of Critique: Any criticism these outlets do offer is surface-level, focusing on buggy launches or poorly received systems. They are loathe to critique the foundational rot—the corporatization, the ideological capture, the subtraction of challenge—because to do so would be to critique the very publishers who grant them traffic-sustaining exclusives. They will report that players are angry, but they will never risk their access by endorsing why the anger is justified.

- The Vacuum of Truth: This creates a suffocating echo chamber for publishers. The only feedback they see is the sanitized, hype-driven coverage from these outlets and their own curated engagement metrics. The genuine, deep-seated dissatisfaction from the player base is filtered out, dismissed as a vocal minority.

The true critic no longer reviews games; he performs last rites. We are not competitors to these stenographers; we are their conscience—a role they abandoned for a seat at the table.

A Flicker in the Darkness: The Hope on the Fringes

The AAA genre is a lost cause. Its fate is sealed by the unholy alliance of corporatization and ideological capture. However, the core desires that fueled the genre have not disappeared. They have simply migrated.

The last, best hope for the MMORPG does not lie with corporate titans. It lies on the fringes:

- The AI Democratization: A new, unpredictable variable has entered the equation: generative AI. For the first time, the astronomical production costs that have gatekept AAA development—concept art, asset creation, voice acting, and even code generation—are beginning to plummet. This technology could radically lower the barrier to entry, empowering small, passionate teams to create worlds with a scope and visual fidelity previously reserved for studios of thousands. Yet, this tool is a double-edged sword. The same technology that empowers a small team also allows the corporate machine to generate oceans of low-effort, procedurally generated content at an unprecedented scale, threatening to replace crafted worlds with AI-powered slop. The fight for the genre’s soul will now extend to who controls and wields this new technology—the craftsman or the corporate committee.

- Indie Projects: Games like Monsters and Memories are being built by developers who remember the old magic. They are attempting to reintroduce risk, player-driven economies, and meaningful social interaction. The ongoing, tumultuous development of Pantheon: Rise of the Fallen, funded directly by player faith, is a testament to the hunger for a world that refuses to capitulate to modern design dogma.

- Private Servers: These communities are living museums, preserving and iterating on classic game designs that the official industry has abandoned.

- Player Communities: The enduring bonds formed in these virtual worlds testify to the power of the original formula. The players are still there, hungry for a real home, their sentiment tracked by aggregate sites and fervent forum discussions that show a clear demographic schism between retail and classic servers.

The future of the virtual world will not be built by committee in a boardroom. It will be built by passionate craftsmen in garages and basements, far from the quarterly reports. They are the keepers of the flame, and their work is a direct rebuke to the false, sanitized reality of the corporate theme park.

The Architecture of Failure: A Warning to Future Builders

The autopsy reveals the cause of death, but a deeper question remains: Why was the patient not saved? How was this systematic dismantling of a beloved art form not just permitted, but actively accelerated? The answer lies not in Irvine or Redmond, but in a broader cultural and economic sickness that enabled the genre’s executioners.

- The Cult of the Shareholder: The doctrine of “shareholder primacy” became the unquestionable religion of corporate America. This ideology asserts a public company’s sole ethical obligation is to maximize value for its shareholders. This provided the moral license for every destructive act. Firing veteran developers, implementing predatory monetization, and gutting creative vision were not seen as betrayal; they were celebrated as fiscally responsible “optimizations.” The player was no longer a participant in a world, but a “user” to be monetized—a data point on a balance sheet. This financialization of art created a system where the most morally corrupt decision was often the most financially rewarded.

- The Rise of the Managerial Class: A new breed of professional manager ascended to power. These were not visionaries or craftsmen; they were CV-optimizing careerists fluent in the jargon of “synergy,” “disruption,” and “paradigm shifts.” Their skill was not creation, but the management of creation. They viewed the passionate, often unruly, creative talent beneath them as a resource to be managed, or more often, a problem to be solved. Their imperative was to eliminate risk, standardize processes, and ensure brand safety, creating the perfect conditions for the rise of the soulless, committee-designed product.

- The Ideological Enablers: The gaming press and academia acted as the system’s enforcers and apologists. Media outlets, dependent on access and advertising, became stenographers for corporate press releases. Simultaneously, academia churned out a generation of critics trained not to analyze gameplay or artistry, but to deconstruct it through a rigid lens of critical theory. They provided the intellectual justification for the purges of “problematic” developers and narratives, painting the corporatization of creativity as a form of social progress. They attacked the genre’s traditional audience as “toxic” for resisting these changes, providing PR cover for studios to abandon their core fans in pursuit of a hypothetical, “better” audience.

- The Captive Audience: The players themselves, through their immense sunk cost—decades of time, money, and emotional investment—became unwitting enablers. Developers bet, correctly, that this loyalty could be abused. They calculated that the community would grumble, protest, and then resubscribe, because the alternative—abandoning a world that was once their home—was too painful. This addiction to legacy was exploited as a strategic asset, a cushion to absorb the backlash from each new act of vandalism against the game’s soul.

The death of the MMORPG was not an accident. It was the logical endpoint of a culture that values metrics over magic, compliance over creativity, and safety over soul. It was allowed to happen because every institution that should have served as a check on corporate power—the media, academia, and even the player base itself—was either co-opted, silenced, or broken. The genre did not just fail; it was sacrificed on the altars of profit and ideology.

Conclusion: The Autopsy is Complete

The state of the MMORPG genre in 2025 is the final result of a broken covenant. The stewards became service providers; the architects of worlds became peddlers of sugar water. The creative heart was stilled by corporatization, the nervous system rewired by ideological dogma, and the voice silenced by a complicit media. The October 28th obituary for Amazon’s MMORPG ambitions is not an anomaly; it is the definitive epitaph for an entire creative paradigm. It is the moment the market formally declared that the covenant is bad for business.

This is not a cry of despair, but a statement of fact. The autopsy is complete. The cause of death is clear. The AAA dream is over. The retreat of Amazon proves the center cannot hold. Now, we look to the fringes, where the real work of resurrection has already begun. The world we lost still exists—in the code, in memory, and in the will of craftsmen operating far from the quarterly reports.

The genre is dead. Long live the genre.

—Wolfshead

The majority of my gaming was in MMOs. Mostly Vanilla WoW, Vanilla ESO and LOTRO.

When I tried New World it felt the opposite of Vanilla WoW. WoW was simple on the surface, but if you dig deeper, you see it’s more complex, wasy for newcomers to get into it and more hardcore players to enjoy it further.

New World to me felt like it was trying to be too complex on the surface to somulate how deep and intricate it is, but deep down, fundamentally it was more simplistic than WoW.

That’s why I didn’t like it, the other was Body Type 1/2 instead of male/female.

The rest of the article clearly point out that the failure of new MMOs is because of the developers or those who decide what the game will be. And If feel like the MMOs released in the past 15 years were made by people who clearly haven’t played MMOs before and don’t understand what the draw of an MMO is.

As such it’s no surprise the games keep failing, because they target an audience that isn’t even interested in playing MMOs, wven newer Asian MMOs are the same – the old ones from 2003 – 2010 were popular, but the current ones aren’t just like Western ones. Because they suffer from the same problem.

Even the single player RPGs have the same problem, before they were about creating a big living world and pushing existing technology to its limit in term of player freedom, where you can go, what you can do. Now this freedom aspect has not only stagnated, it has atrophied and degenerated into what is inferior to the same counterparts from 20 years ago. Now games are all about graphics and voice acting, but if you take away those and replace them with graphics from 2002 and no voice acting, the new games from 2025 will look more inferior and simplistic than those made in 2002.

Such is the state of gaming in my opinion. It had its golden age, now it’s in creative decline as the developers are just not talented enough to make something good or better. If you have to compare new games to 20 year old games and the 20 year old games win, then it’s pretty sad.

Somwone might say Elden Ring is good, but to me The Elder Scrolls 3 Morrowind is much better and I think it’s better than every single RPG released in the last 20 years.

So I just play old games and don’t even feel sad that gaming is dead.

I only play old games too. I only watch old TV and film too. I can no longer bear anything that reeks of modernity.

Allwynd is quite right. Modern MMOs often try to fake the facade of previous MMOs. Design philosophy and all that, it went out of the window quite a while ago already.

This makes me very, very sad. And angry. Young players get fed such a load of drivel today, it is heartbreaking. I was born and grew up in blessed times, not only MMOs were thriving, games were amazing.

Today games might even turn their gamers dumb, given the way they are designed and monetized.

New World got an amazing final expansion, a farewell. The near and mid and perhaps even long term future of MMOs is dire. There won’t be anything on another level with EQ, WoW, Ultima Online, Dark Age of Camelot…

Isn’t it an irony and tragedy, hardware, software, internet, it all got so much better and then… we get served really bad games. Add woke heroines to add to the insult.

Also see “Legion Remix”. The kinda in between expansion that is more popular even among WoW players than the main game by now.

Let me cite AI:

Legion Remix is a “power fantasy” rather than an MMO is accurate because the event’s core design emphasizes rapid character progression and becoming overpowered through a special, account-wide artifact system, which is a shift from the typical slow-and-steady MMO experience. Players can quickly gain powerful abilities and gear, making them feel extremely potent, and the primary end-game rewards are cosmetics like mounts and transmog, not gear upgrades.

Such a tragedy. We witness the Dark Ages of Gaming. The MMO Empire has finally fallen. The “Classical Antiquity/Period” with its incredible highs, as in history, is over. The only solace I can offer is that the historical Dark Ages were not all that dark either, Christianity endured and kept science, faith, traditions etc. alive. I am just afraid we will not even see the new “Middle Ages” of gaming.

I hope that I will live long enough to see this new age of gaming and that it will make me drool and talk about and dream about like the MMOs of my youth!

I agree!